Three years ago, we decided ramp up internal app development at Philips Hue. After interviewing candidates (78!) for six months, I became the lead Android developer of the freshly hired Android team.

In this non-tech post (for a change), I’d like to openly share my experiences being a team lead. It’s been a bumpy ride, but I came out with quite some new perspectives that make me a stronger lead and a better person.

Part 1: Team and project#

To put my experiences into perspective, I think it’s important to first cover the team set up, my role and some of the project history.

Feel free to skip this part and jump to the learnings instead 👇!

Team setup and my role#

Our team was a component team, responsible for building the Philips Hue Android app. Consisting of both quality assurance (QA) and developers, the team size was significant.

Now to be clear, I wasn’t the team manager and hence didn’t do many typical managers related activities:

- I didn’t ensure people follow corporate processes (e.g. time writing)

- I didn’t make practical arrangements for people (e.g. order hardware)

- I didn’t approve leave/conferences/…

- I didn’t do evaluation and career planning meetings

- …

This was a very deliberate choice to be a part of the team instead of boss-of, I strongly wanted to stay on the technical career path.

I write code, not manage people.

Instead, my role was to write code (!), drive the Android app structurally forward (tech debt/architecture) and coach team members to help them grow.

A rough start#

From day one, the project was met with many different challenges.

First of all, the existing source code stemmed from our start up days and had a very weak architecture with a very high coupling between classes. Hence, refactoring often created side effects in other parts of the code.

How on Earth do we make this app better if every change we make has unintended side effects?

To make matters worse, this happened at a time where the tech stack on Android was changing rapidly: Kotlin, architecture components, modularization, RXJava… So which one of these should we adopt? How do we build up the knowledge in the team? And with which one do we start?

How on Earth do we make this app better if we don’t know where to start?

Secondly, our build infrastructure was slow and unstable. These slow and flaky builds made it very painful to integrate new changes. On top of that, we had the habit of creating extremely huge pull requests (for various reasons) which were nearly impossible to review.

How on Earth do we make this app better if integrating pull requests is tedious?

Thirdly, the Philips Hue business was incredibly ambitious and wanted features to be delivered fast. This resulted in many projects being executed in parallel (including a full app UI makeover by a different team!). But as a team, we were still struggling to agree on a future vision/architecture for the app.

How on Earth do we make this app better if we can’t agree on a clear architecture vision?

And to make matters worse, we didn’t have a grip on the app quality! Hence a lot of slow manual testing was required that would find a lot of regression bugs. These bugs would often be found late, making it very difficult to fix them without breaking something else.

How on Earth do we make this app better if we struggle to release?

Finally, we had chosen to refactor our app instead of rewriting it. But because of the sheer amount of technical depth we had this refactoring was only providing limited results. For sure our codebase was (slowly) improving, but to put it bluntly, the results weren’t motivating the team.

How on Earth do we make this app better if people lose their motivation?

Part 2: Lessons learned#

While we managed to solve all of these challenges (and more), I don’t want to cover the solutions to these in this post. Rather I’d like to talk about what I learned as a lead along the way as these learnings will be more universally applicable.

1. Acknowledge the bad#

All of these challenges were frustrating people… and with reason. However, as a team, this pushed us into a negative, complaining mode which wasn’t very motivating either. Arguably, complaining was even making it worse… even causing a downwards spiral.

On the other hand though, we were making things better and being able to successfully push back on many business decisions that would have made our lives even more challenging.

As the negative was clearly overshadowing the positive, I always tried to spin it positively and emphasize our successes (as small as they may have been). And the harder people complained, the more I tried to spin it…

But despite my good intentions however, in my spinning I came across as dismissive of other people’s complaints. It’s not because we had a few minor successes that all our other challenges weren’t real anymore. Even worse, I made people feel as if they didn’t have the right to complain.

Once the dust settles down, try to open a constructive conversation on how to make things better. One of my favorite questions here is: “What will we do differently tomorrow to make this better?”

2. Focus on your happiness#

Another thing I used to do is try and shield the team from all distractions that were happening around them. So I would attend the reporting meetings, write all documentation myself, pick up the dull tasks nobody else wanted to do,… All just so the team could do what they love doing most: writing awesome code!

However, by always putting myself last I wasn’t getting a lot of job satisfaction anymore. Being overloaded with “dull work” wasn’t just demotivating, but by not involving others you also miss the opportunity to get their buy-in. For instance, if you document something, others will be more inclined to keep the documentation up to date if they co-authored it in the first place.

And it turns out that having low energy levels myself, also influences how I’m able to impact the rest of the team. So I decided to drop quite a few of my tasks or delegate them to others so that I could also focus on writing more code. This brought me closer to the team, made me feel happier and increased my energy level to empower people to drive things forward.

Examples of tasks I delegated are architecture documentation, architecture plans, attending feature team meetings, redirect external questions to other team members, giving access to tools, high-level estimations…

Examples of tasks I stopped doing: one on ones. That was a tough decision, but at some point, I realized that trying to help individual members in the team wasn’t helping the team as a whole. Instead, I created a culture where any one from the team could interrupt me and ask questions at any time.

I do want to stress that helping team members was always my highest priority and I would instantly drop anything to help them out. However, doing structural one on ones was the responsibility of their manager.

3. Be transparent#

As part of my role I had quite some non developer related work, whether it was reporting to upper management, early-stage planning of new features, aligning between teams, high-level estimates…

Usually, I didn’t want to bother the team with this information. E.g. My thinking was that people could feel extra pressured once they knew management was asking for regular status updates.

There are actually two big drawbacks doing so:

- If you don’t tell people what’s up, they will start assuming themselves.

- My stand up reports often made it look like I wasn’t doing anything.

So instead I decided to just be completely open and transparent about everything. Even top-level decisions like: “we need to let go of some of our (contractor) team members” or “management isn’t happy with the current speed of development”, I would communicate as quickly and openly as possible and offer people to ask any questions about it.

To give you an idea of how far I took this: I even disclosed to my team that I felt I struggled in my role and decided to find some help. So, one day, during stand up I shared that I started following coaching to do my job better and that I would be spending a considerable amount of time doing so.

Opening up like that made me feel very vulnerable (and my direct approach definitely surprised some team members). But the team really appreciated the openness and respected me for taking my job seriously.

4. Lead by example#

During our standup, I would say I was going to do X, but because I had so many interruptions and meetings, I often never got around to actually doing it. This was especially inconvenient during times where we struggled to get things done and make our codebase better.

Actually, this even made it seem like special rules applied to me! How can I expect us as a team to deliver on our committed work if I don’t deliver on my commitments myself?

While this is (in retrospect) my most obvious learning, in practice it hit me quite hard when I got this feedback… But I learned and even though it was hard to turn around, I now deliver on what I say I will. Which, in my case, involves saying no or postponing/delegating other work.

5. Team building#

Something I strongly believe in is that a happy team is (almost) all you need to be successful as a team. When people are having fun and get fulfillment from their work, they take pride and ownership in what they do and will do things right.

One very important aspect of that is to ensure that people also hang out in a non-work context. This doesn’t just build trust between them, but it also increases the fun!

And this can be done in very simple ways! I would trigger the team at least once per week to all walk over to the coffee bar on our campus together. Or we also organized cultural lunches (as we have a lot of different nationalities in the team), where a team member would book lunch in a restaurant the country of origin.

Getting closer together as a team increased the trust between people and the fun we were having. To me this is probably the biggest reason why we ended up being successful. We managed to fully integrate testers and developers, everyone took their share of dull work and we made everyone jointly accountable for app quality.

Interestingly, “building a team” wasn’t part of my original role. Over time though, I realized that this is also a key part of being a lead. However, I made sure not to organize most events myself, I just made sure someone was.

6. Leverage the power of the team#

There’s so much more that you can get done as a team than you can accomplish by yourself. So don’t be afraid to ask team members for help, advice and even delegate things.

Sure, the delegated work doesn’t get done exactly as you would have done it, but that’s exactly the strength! At the very least it’s an opportunity to coach and help a team member. Whereas at the other end of the spectrum the result is way better than what you would have done in the first place. E.g. I was blown away by the business case one of our testers made to scale up our Firebase test lab tests to more devices.

What might seem dull to you (as you’ve done it so many times), could actually be an opportunity for another team member, a way for them to step up and take on more responsibility.

I’ve learned that my team is really the most valuable asset I have as a lead, as such they are also the primary indicator to tell me how things are going.

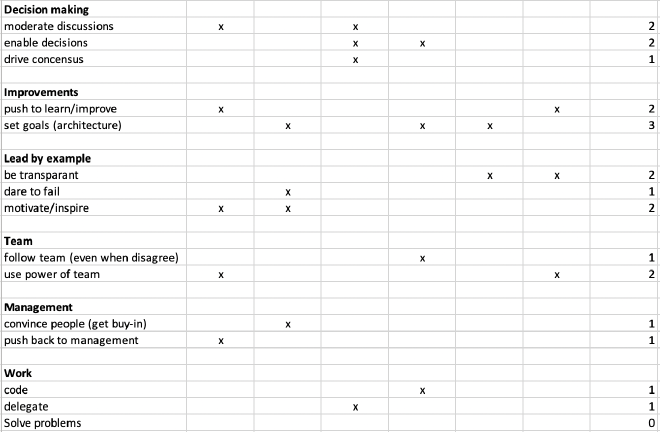

But how can I know that I’m being a good lead? Is there maybe something I could do better? Or even… what does the team expect their lead to do in the first place? Well… just ask them.

I asked my team a while ago what they expected me to do (see below) and interestingly enough, nobody expected me to solve our technical problems. Instead, they wanted me to facilitate decision making and ensure we have a clear architecture goal to work towards.

So I took their advice and changed my priorities.

7. Have faith#

To be fair, my tenure as a lead developer definitely wasn’t a walk in the park. The legacy code and inconvenient timings of internal projects proved to be a real challenge and strongly affected our team mindset. And once a team gets in a negative vibe, it is very hard to turn that around.

Personally, I struggled with this for quite some time and tried hundreds of ideas to make things better. One of such was biweekly workshops to learn something new. This came from the insight that different team members felt they weren’t learning enough. That ended up boosting team spirit and accelerating our Architecture components, RXJava, and Kotlin adoption.

But in the end, I, no matter how hard I tried, I wasn’t able to turn things around fast enough… And frankly, we lost quite some amazing developers along the way. Seeing people leave as a lead is… well… very painful.

I’m very happy to have reached out for help and to have found a great coach. For six months, we did monthly sessions which I prepared and took homework from. And that opened my mind to a lot of different perspectives and exposed me to even more of my own flaws.

Thanks to the coaching, my always positive attitude and a lot of perseverance, we managed to book our first successes:

- Move over to biweekly releases

- Start using Architecture components & Kotlin

- Get a stable set of Espresso tests

And funny thing, because of these successes, people actually slowly but surely started to believe! Almost like a self-fulfilling prophecy we were able to stack up success after success:

- Build, test and upload releases in under 12 min

- Rewrote the key screens of our app

- Dramatically sped up app startup

- Decreased app size by 65%

- over 30 modules and 35% Kotlin

- close to 200 stable integration tests

- …

Learning 7: getting to a cohesive, highly performant and fun team can be quite challenging. But have faith, stay positive, persist and reach out for help. Together as a team, you can do this!

*. Other learnings#

To keep the length of this post under control, I’m just going to briefly mention my runner-up learnings:

- Refactoring isn’t a very motivating activity

- ➡️ We tackled this by splitting our app in modules (“vertical slices”). This allows to aggressively rewrite parts of our app or isolate legacy code in dedicated modules.

- Avoid rehashing the same discussions over and over

- ➡️ We tackled this by very concisely documenting decisions and their rationale. Next time we would start rehashing the same discussion, I would intervene and say: “last time we decided this for that reason, do we have any new insights to reopen this discussion?”

- All team members are equal

- ➡️ Doesn’t matter whether they are contractors or on the payroll, anyone gets the same opportunity to make their mark on the project and gets proper feedback and support from me.

- ➡️ Also as a team lead I don’t have any more to say than any other developer, nor do they have any more to say than one of our QA engineers. We are all jointly accountable for app quality and releasing on time. Either we all fail or success together.

- Celebrate success

- ➡️ It’s so easy to get dragged along in the day to day operations that you fail to appreciate what you accomplish as a team. Therefore I keep a dedicated confluence page where I keep track of every success (e.g. high app version rating, sped up app startup,…). I regularly share this with the team (on Slack) and even the rest of the organization.

- Leverage existing solutions

- ➡️ While tackling our technical challenges, we cooked up some custom solutions to already solved problems (e.g. a custom MVP implementation optimized for A/B testing). But this introduced a lot of complexity and increased the learning curve. Eventually, we just settled with vanilla Android architecture components, a simple solution that worked well out of the box.

- It’s totally fine not to do things

- ➡️ Quite regularly, we would say we were going to do a particular thing (e.g. more pair programming), but we never ended up doing it. That’s totally fine. A key reason why some things don’t happen is often that people don’t fundamentally believe in them, but instead think we should do them to please others. Well, you shouldn’t. Just try to be open and explicit about what you actually will and won’t do.

What’s next#

With everything we’ve learned building our mobile engineering culture at Philips Hue, we’ve got some very exciting stuff in the pipeline. Make sure to follow the Philips Hue engineering medium to catch it!

Wrap-up#

Two years in being a team lead, I’m incredibly proud of what we accomplished as a team: we can release ridiculously fast, dramatically improved our codebase, streamlined our processes and increased our output by a factor of 4x. This isn’t just visible in the joy/pride the team takes in working on our app, but user sentiment is also going up fast.

The ride to get there was rough though and despite my good intentions, I made many mistakes. However, by keeping on investing in the team and myself we were able to get our app on track!

One of my long open career goals was to work in a high performant team on a world-class product. And I’m happy to say that I can now finally check that box!!! Though, I didn’t expect to be leading that team.

Hopefully, you liked this honest retrospective, feel free to leave a comment below or follow me on Mastodon.